3. Familiarize Ourselves With The Data¶

Let's get our hands on some data so we can see with our own eyes what HiFi and UL data look like.

Create A Directory

Load modules

code

Subset Our Input Data

In order to get a feel for the data, we only need a small portion of it. Pull the first few thousand reads of the HiFi reads and write them to new files.

code

Next, downsample the ONT UL reads, too.

code

Now let's compare the data

We are going to use a tool called NanoComp. This tool can take in multiple FASTQs (or BAMs) and will create summary statistics and nice plots that show things like read length and quality scores. NanoComp has nano in the name, and has some ONT-specific functionality, but it can be used with PacBio data just fine.

code

Once the run is complete (~2 minutes), navigate in your file browser to the folder that NanoComp just created and then click on the NanoComp-report.html file (near the bottom of the folder's contents) to open it. Take a look at the plots for log-transformed read lengths and basecall quality scores. (Note that you may have to click Trust HTML at the top of the page for the charts to display.)

What is the range of Q-scores seen in HiFi data?

The mean and median Q-scores are around 33 and 34, but there is a spread. The CCS process actually produces different data based on a number of different factors, including the number of times a molecule is read (also called subread passes). Raw CCS data is usually filtered for >Q20 reads at which point it is by convention called HiFi. (Note that some people use CCS data below Q20!)

What percent of UL reads are over 100kb?

This depends on the dataset but it is very common to see 30% of reads being over 100kb. The 100kb number gets passed around a lot because reads that are much longer than HiFi are when UL distinguishes itself.

Cleaning Data For Assembly¶

PacBio Adapter Trimming¶

PacBio's CCS software attempts to identify adapters and remove them. This process is getting better all the time, but some datasets (especially older ones) can have adapters remaining. If this is the case, adapters can find their way into the assemblies.

Run CutAdapt to check for adapter sequences in the downsampled data that we are currently using. (The results will print to stdout on your terminal screen.)

code

Notice that we are writing output to /dev/null. We are working on a subset of these reads so the runtime is reasonable. There is no need to hold onto the reads that we are filtering on, it is just a subset of the data.

What do you think the two sequences that we are filtering out are? (hint: you can Google them)

The first sequence is the primer and the second sequence is the hairpin adapter. You can see the hairpin by looking at the 5' and 3' ends and checking that they are reverse complements.

Why can we get away with throwing away entire reads that contain adapter sequences?

As you can see from the summary statistics from CutAdapt, not many reads in this dataset have adapters/primers. There is some concern about bias—where we remove certain sequences from the genome assembly process. We've taken the filtered reads and aligned them to the genome and they didn't look like they were piling up in any one area.

What would happen if we left adapter sequences in the reads?

If there are enough adapters present, you can get entire contigs comprised of adapters. This is not the worst, actually, because they are easy to identify and remove wholesale. It is trickier (and this happens more often) when adapter sequences end up embedded in the final assemblies. If/when you upload assemblies to repositories like Genbank they check for these adapters and force you to mask them out with N's. This is confusing to users because it is common to use N's to signify gaps in scaffolded assemblies. So users don't know if they are looking at a scaffolded assembly or masked out sequence.

ONT Read Length Filtering¶

Hifiasm is often run with ONT data filtered to be over 50kb in length, so let's filter that data now to see how much of the data remains.

code

Now we can quickly check how many reads are retained.

code

When we filter for reads over 50kb, how many reads and total base pairs of DNA are filtered out?

Over half of the reads are filtered out, but only about 25% of the data (see "Total bases") is filtered. This makes sense as the long reads contribute more bp per read.

Verkko is typically run without having filtered by size, why do you think that is?

Based on the answer to the last question, filtering an ultralong readset for >50kb reads does not reduce the overall size of the dataset very much.

Phasing Data¶

Now that we've introduced the data that creates the graphs, it's time to talk about data types that can phase them in order to produce fully phased diploid assemblies.

At the moment the easiest and most effective way to phase human assemblies is with trio information. Meaning you sequence a sample, and then you also sequence its parents. You then look at which parts of the genome the sample inherited from one parent and not the other. This is done with kmer databases (DBs). In our case, we will use both Meryl (for Verkko) and yak (for hifiasm) so let's take a moment to learn about kmer DBs.

Trio data: Meryl¶

Meryl is a kmer counter that dates back to Celera. It creates kmer DBs, but it is also a toolset that you can use for finding kmers and manipulating kmer count sets. Meryl is to kmers what BedTools is to genomic regions.

Today we want to use Meryl in the context of creating databases from PCR-free Illumina readsets. These can be used both during the assembly process and during the post-assembly QC.

Helpful Background¶

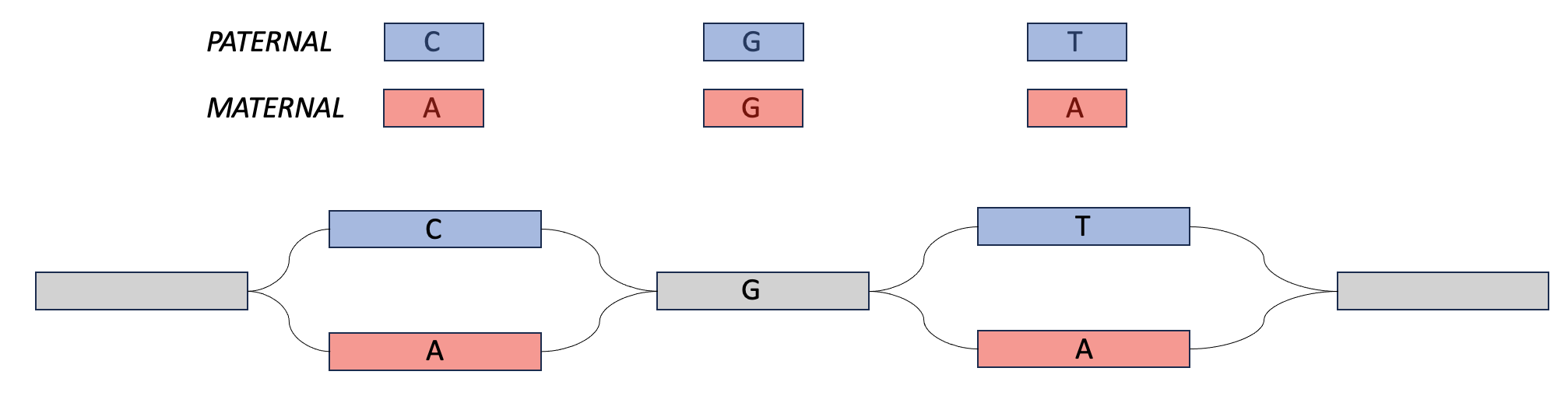

Meryl can be used to create hapmer DBs (haplotype + k-mer), which can be used as input for tools like Verkko and Merqury. Hapmer DBs are constructed from the k-mers that a child inherits from one parent and not the other. These k-mers are useful for phasing assemblies because if an assembler has two very similar sequences, it can look for maternal-specific k-mers and paternal-specific k-mers and use those to determine which haplotype to assign to each sequence.

In the Venn diagram above, the maternal hapmer k-mers/DB are on the left-hand side (in the purple in red box). The paternal hapmer k-mers/DB are on the right-hand side (in the purple in blue box).

Wait, what is phasing?

Phasing is the process of saying two things are on the same haplotype (i.e., saying two blocks of sequence came from the maternal haplotype, or vice versa)

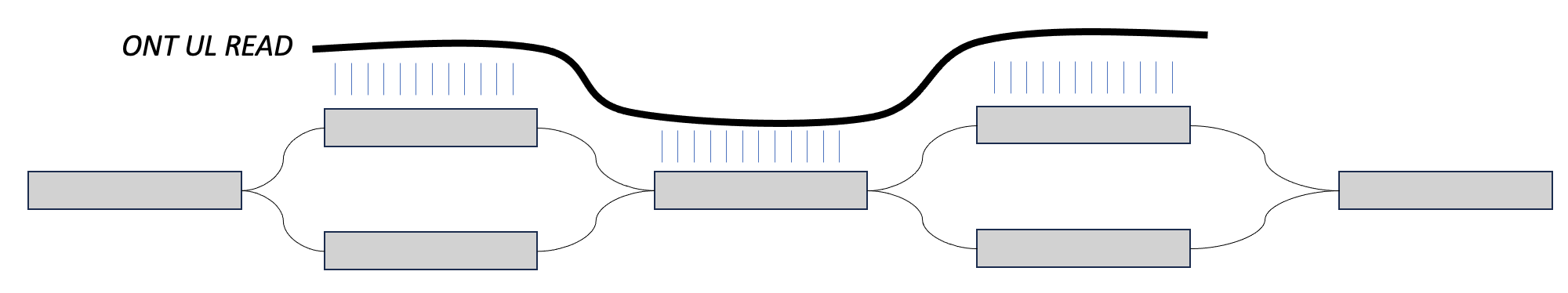

One way you will hear us talk about phasing in this workshop is in the context of ultra long reads. In this case, we may have two heterozygous regions separated by a homozygous region. When an assembler is walking this graph, if there is no external information about haplotype, then the assembler doesn't have a way of knowing that certain blocks of sequence came from the same sequence. For example, in the bottom image, the assembler might walk from the top left block, into the homozygous block, and then down to the bottom right block, switching between the two haplotypes.

However, if we can find a long read that maps to the top sequences in both, then we could say that these sequences come from the same haplotype. That is phasing.

We can play a similar trick with parental data. If we find paternal markers in both sequences in the top, then we can say that they both come from the paternal haplotype. This is also phasing.

Using Meryl¶

Make sure you are in the right directory

Now create a small file to work with

code

Create a k-mer DB from an Illumina read set

code

This should be pretty fast because we are just using a small amount of data to get a feel for the program. The output of Meryl is a folder that contains 64 index files and 64 data files. If you try and look at the data files you'll see that they aren't human readable. In order to look at the actual k-mers, you have to use meryl to print them.

Look at the k-mers

The first column is the k-mer and the second column is the count of that k-mer in the dataset.

Take a look at some statistics for the DB

We see a lot of k-mers missing and the histogram (frequency column) has a ton of counts at 1. This makes sense for a heavily downsampled dataset. Great. We just got a feel for how to use Meryl in general on subset data. Now let's actually take a look at how to create Meryl DBs for Verkko assemblies.

How would we run Meryl for Verkko?

Here is what the Slurm script would look like:

(Don't run this, it is slow! We have made these for you already.)

code

#!/bin/bash -e

#SBATCH --account nesi02659

#SBATCH --job-name meryl_run

#SBATCH --cpus-per-task 32

#SBATCH --time 12:00:00

#SBATCH --mem 96G

#SBATCH --partition milan

#SBATCH --output slurmlogs/%x.%j.out

#SBATCH --error slurmlogs/%x.%j.err

module purge

module load Merqury/1.3-Miniconda3

export MERQURY=$(dirname $(which merqury.sh))

## Create mat/pat/child DBs

meryl count compress k=30 \

threads=32 memory=96 \

maternal.*fastq.gz \

output maternal_compress.k30.meryl

meryl count compress k=30 \

threads=32 memory=96 \

paternal.*fastq.gz \

output paternal_compress.k30.meryl

meryl count compress k=30 \

threads=32 memory=96 \

child.*fastq.gz output \

child_compress.k30.meryl

## Create the hapmer DBs

$MERQURY/trio/hapmers.sh \

maternal_compress.k30.meryl \

paternal_compress.k30.meryl \

child_compress.k30.meryl

Closing notes

It should be noted that Meryl DBs used for assembly with Verkko and for base-level QC with Merqury are created differently. Here are the current recommendations for k-mer size and compression:

- Verkko: use

k=30and thecompresscommand - Merqury: use

k=21and do not include thecompresscommand

Why does Verkko use compressed Meryl DBs while Merqury does not?

The biggest error type from long read sequencing comes from homopolymer repeats. So assembly graphs are typically constructed from homopolymer compressed data. After the assembly graph is created the homopolymers are added back in. Verkko compresses the HiFi reads for you, but you need to give it homopolymer compressed Meryl DBs so they play nicely together. Merqury on the other hand is used to assess the quality of the resultant assembly, so you want to keep those homopolymers in order to find errors in them.

Why does Merqury use k=21 ?

Larger K sizes give more conservative results, but this comes at a cost since you get lower effective coverage. For non-human species, if you know your genome size you can estimate an optimal K using Meryl itself. If you are wondering, Verkko uses k=30 in order to be "conservative". And at the time of writing this document, different species typically stick with k=30. Though this hasn't been tested, so it may change in the future.

Do Meryl DBs have to be created from Illumina data? Could HiFi data be used an an input to Meryl?

They don't! You can create a Meryl DB from 10X data or HiFi data, for instance. The one caveat is that you want your input data to have a low error rate. So UL ONT data wouldn't work.

Other things you could do with Meryl

Here is an example of something you could do with Meryl:

- You can create a k-mer DB from an assembly

- You could then print all k-mers that are only present once (using

meryl print equal-to 1) - Then write those out to a bed file with

meryl-lookup. Now you have "painted" all of the locations in the assembly with unique k-mers. That can be a handy thing to have lying around.

Trio data: Yak¶

Yak (Yet-Another Kmer Analyzer) is the kmer counter that we need for Hifiasm assemblies and to QC assemblies made with either assembler so let's learn about how to make yak dbs.

In the Meryl section we subset R1, now subset R2 as well

code

Look up yak's github and figure out how to make a count/kmer db for this data

Yak won't work on our Jupyter instances, so create a slurm script that has 32 cores and 96GB of memory. That way it will work on our subset data and it will also work on full size data -- you'd just have to extend the time variable in slurm.

Click here for the answer

Here is one way to call yak in a yak.sl script...

#!/bin/bash -e

#SBATCH --account nesi02659

#SBATCH --job-name yak_run

#SBATCH --cpus-per-task 32

#SBATCH --time 00:10:00

#SBATCH --mem 96G

#SBATCH --partition milan

#SBATCH --output slurmlogs/%x.%j.out

#SBATCH --error slurmlogs/%x.%j.err

module purge

module load yak/0.1

yak count \

-t32 \

-b37 \

-o HG003_subset.yak \

<(zcat HG003_HiSeq30x_5M_reads_R*.fastq.gz) \

<(zcat HG003_HiSeq30x_5M_reads_R*.fastq.gz)

Notice that for paired-end reads we have to stream both reads to yak twice!

If you haven't already, execute your yak script using slurm (takes about 2 minutes).

When you are done you get out a non-human readable file. It doesn't need to be compressed or decompressed, and nothing else needs to be done in order to use it.

Closing remarks on yak

- If you have Illumina data for an entire trio (which we do), then you can use yak to make yak DBs for each parent separately to use hifiasm for trio assembly or yak trioeval for quality control (more on that later)

- You don't need to homopolymer compress yak dbs

- There is no need to create separate dbs for assembly and for QC

- yak can perform a variety of assembly QC tasks (as we will see) but it isn't really designed to play around with kmers like Meryl is

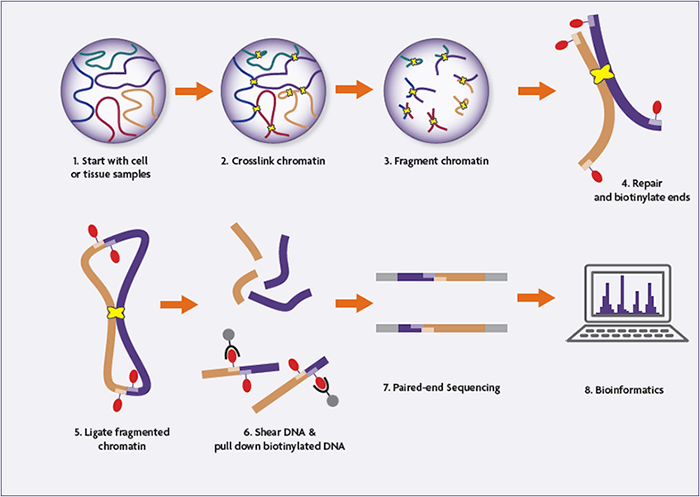

Hi-C¶

Hi-C is a proximity ligation method. It takes intact chromatin and locks it in place, cuts up the DNA, ligates strands that are nearby and then makes libraries from them. It's easiest to just take a look at a cartoon of the process.

Given that Hi-C ligates molecules that are proximate (nearby) to each other, it can be used for spatial genomics applications. In assembly, we take advantage of the fact that most nearby molecules are on the same strand (or haplotype) of DNA.

What are the advantages of trio phasing over Hi-C?

Trio data is great for phasing because you can assign haplotypes to maternal and paternal bins. This has the added benefit of assigning all maternal contigs to the same assembly. Hi-C ensure that an entire chromosome is phased into one haplotype, but across chromosomes the assignment is random.

So why wouldn't you always use trio data for phasing?

It can be hard to get trio data. If a sample has already been collected it may be hard to go back and identify the parents and collect sample from them. In non-human samples, trios can also be difficult particularly with samples taken from the wild.

Are there any difficulties in preparing Hi-C data?

Yes! As you can see in the cartoon above Hi-C relies on having intact chromatin as an input, which means it needs whole, non-lysed cells. This means that cell lines are an excellent input source, but frozen blood is less good, for instance.

Other (Phasing) Datatypes¶

We should also mention that there are other datatypes that can be used for phasing, though they are less common.

Pore-C

Pore-C is a variant of Hi-C which retains the chromatin conformation capture aspect, but the sequencing is done on ONT. This allows long-read sequencing of concatemers. Where Hi-C typically has at most one "contact" per read, Pore-C can have many contacts per read. The libraries also do not need to be amplified, so Pore-C reads can carry base modification calls.

StrandSeq

StrandSeq is a technique that creates sparse Illumina datasets that are both cell- and strand-specific. Cell specificity is achieved by putting one cell per well into 384-well plates (often multiple). Strand specificity is achieved through selective fragmentation of nascent strands. (During DNA replication, BrdU is incorporated exclusively into nascent DNA strands. In the library preparation the BrdU strand is fragmented and only the other strand amplifies.) This strand specificity gives another way to identify haplotype-specific kmers and use them during assembly phasing.

If you are interested in these phasing approaches, you can read more about them in the following articles:

-

Lorig-Roach, Ryan, et al. "Phased nanopore assembly with Shasta and modular graph phasing with GFAse." bioRxiv (2023): 2023-02.

-

Porubsky, David, et al. "Fully phased human genome assembly without parental data using single-cell strand sequencing and long reads." Nature biotechnology 39.3 (2021): 302-308.