Automated version control

- Version control is like an unlimited ‘undo’.

- Version control also allows many people to work in parallel.

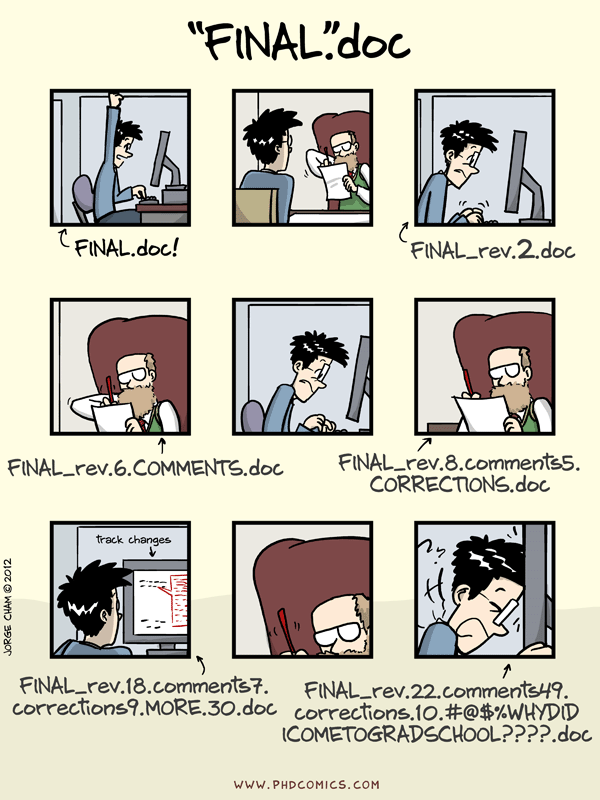

We’ll start by exploring how version control can be used to keep track of what one person did and when. Even if you aren’t collaborating with other people, automated version control is much better than this situation:

We’ve all been in this situation before: it seems unnecessary to have multiple nearly-identical versions of the same document. Some word processors let us deal with this a little better, such as Microsoft Word’s Track Changes, Google Docs’ version history, or LibreOffice’s Recording and Displaying Changes.

Version control systems start with a base version of the document and then record changes you make each step of the way. You can think of it as a recording of your progress: you can rewind to start at the base document and play back each change you made, eventually arriving at your more recent version.

Once you think of changes as separate from the document itself, you can then think about “playing back” different sets of changes on the base document, ultimately resulting in different versions of that document. For example, two users can make independent sets of changes on the same document.

Unless multiple users make changes to the same section of the document - a conflict - you can incorporate two sets of changes into the same base document.

A version control system is a tool that keeps track of these changes for us, effectively creating different versions of our files. It allows us to decide which changes will be made to the next version (each record of these changes is called a commit), and keeps useful metadata about them, such as who made the change. The complete history of commits for a particular project and their metadata make up a repository. Repositories can be kept in sync across different computers, facilitating collaboration among different people.

Automated version control systems are nothing new. Tools like RCS, CVS, or Subversion have been around since the early 1980s and are used by many large companies. However, many of these are now considered legacy systems (i.e., outdated) due to various limitations in their capabilities. More modern systems, such as Git and Mercurial, are distributed, meaning that they do not need a centralized server to host the repository. These modern systems also include powerful merging tools that make it possible for multiple authors to work on the same files concurrently.

Git was created by Linus Torvalds in 2005 as an alternative to BitKeeper, one of the first distributed version control systems, to track changes in the Linux kernel. Torvalds provided several explanations of the name, of varying degrees of politeness, which are enumerated in the project’s README, including “Global Information Tracker” for when “you’re in a good mood”.

For those interested, The Carpentries has a Version Control with Mercurial lesson (2013-2018), which provides additional context and historical perspective.